In response to David Harding’s “Work as if you live in the early days of a better society”, featured in Magic Moments: Collaboration between artists and young people, by Anna Harding (ed.),Black Dog Publishing, 2005.

What would the early days of a better society be like? What am I doing in this not so imaginary place?

My most poignant imagining reveals faces, all of which are lit by excitement that comes from an engagement in activities both ambitious and seemingly incidental. My place amongst this scenario is to be one of those that encourages or introduces the excitement. One could assume that because I am an artist, my role would be restricted to a creative activity but this need not be so. The key question is: What is needed to get people excited?

The purpose of this text is not to find a generalising solution to this question but rather to begin a thought process about how one can encourage the most fruitful engagement between an individual and that which interests them. This blog has already introduced the project which led me to stumble across this article. I intend the questions and thoughts that I come up with to act as a background discussion for the ongoing development of proposals and activities for the opening of the Dalry Primary School.

David Harding’s incentive was to address ‘social inclusion’ with respect to art and more broadly a sense of place and identity within schools and localised communities. The understanding that I have of ‘social inclusion’ from this article and that which I will base my thoughts on are: that ‘social inclusion’ means to bring in the poor, underprivileged and outcast into an arena where they are appreciated as people in their own right. I should point out that the article established that many of the individuals targeted were also considered underachievers or disruptive. I have to admit to finding the term ‘social inclusion’ problematic, this is principally because it automatically assumes a labelling function for those that would be targeted. It promotes a proposition that individuals could have the opportunity to redeem themselves from their inferior position. To avoid this condescending approach, first and foremost an activity must exist, whether it be in a development stage or in action, that the individual can engage with and consider. This then encourages or instigates the notion of choosing to invest energy in something that could lead to further possibilities. Moreover the individual making the choice is doing so because it is their own will and because they want something more than they currently have.

Although Harding uses the term ‘social inclusion’ he has also recognised that people should not be pigeonholed or forced into scenarios that hold little or no personal interest. One cannot enter into a project projecting expectations on those that take part and similarly one cannot have overarching expectations of the inherent good that a project may bring about. Instead the project should simply be something of interest, first and foremost to the organisers but also to those that take part. It is enough that belief and conviction steer the content and energy of a project that is open to others to see and take part. The resultant energy and conviction will become attractive to others and lead them to consider investing themselves in it.

I will refer to a quote that Graham Hayward sent me from ‘Ivan Illich, Deschooling Society’, this is also a title that David Harding referred to in his essay.

Phenomenology of School P26 “1. Age School groups people according to age. This grouping rests on three unquestioned premises. Children belong in school. Children learn in school. Children can be taught only in school. I think these unexamined premises deserve serious questioning. We have grown accustomed to children. We have decided that they should go to school, do as they are told, and have neither income or families of their own. We expect them to know their place and behave like children. We remember, whether nostalgically or bitterly, a time when we were children, too. We are expected to tolerate the childish behaviour of children. Mankind, for us, is a species both afflicted and blessed with the task of caring for children. We forget, however, that our present concept of “childhood” developed only recently in Western Europe and more recently still in the Americas. Childhood as distinct from infancy, adolescence, or youth was unknown to most historical periods. Some Christian centuries did not even have an eye for its bodily proportions. Artists depicted the infant as a miniature adult seated on his mother’s arm. Children appeared in Europe along with the pocket watch and the Christian money lenders of the Renaissance. Before our century neither the poor nor the rich knew of children’s dress, children’s games, or the child’s immunity from the law. Childhood belonged to the bourgeoisie. The worker’s child, the peasant’s child, and the nobleman’s child all dressed the way their fathers dressed, played the way their fathers played, and were hanged by their neck as were their fathers. After the discovery of “childhood” by the bourgeoisie all this changed. Only some churches continued to respect for some time the dignity and maturity of the young. Until the Second Vatican Council, each child was instructed that a Christian reaches moral discernment and freedom at the age of seven, and from then on is capable of committing sins for which he may be punished by an eternity in Hell. Toward the middle of this century, middle-class parents began to try to spare their children the impact of this doctrine, and their thinking about children now prevails in the practice of the church. Until the last century, “children” of middle-class parents were made at home with the help of preceptors and private schools. Only with the advent of industrial society did the mass production of “childhood” become feasible and come within the reach of the masses. The school system is a modern phenomenon, as is the childhood it produces. Since most people today live outside industrial cities, most people today do not experience childhood. In the Andes you till the soil once you have become “useful”. Before that, you watch the sheep. If you are well nourished, you should be useful by eleven, and otherwise by twelve. Recently, I was talking to my night watchman, Marcos, about his eleven-year-old son who works in a barbershop. I noted in Spanish that his son was still a “nino”. Marcos, surprised, answered with a guileless smile: “Don Ivan, I guess your right”. Realizing that until my remark the father had thought of Marcos primarily as his “son”, I felt guilty for having drawn the curtain of childhood between two sensible persons. Of course if I were to tell the New York slum dweller that his working son is still a “child”, he would show no surprise. He knows quite well that his eleven-year-old son should be allowed childhood, and resents the fact that he is not. The son of Marcos has yet to be afflicted with the yearning for childhood; the New Yorker’s son feels deprived. Most people around the world, then, either do not want or cannot get modern childhood for their offspring. But it also seems that childhood is a burden to a good number of those who are allowed it. Many of them are simply forced to go through it and are not happy playing the child’s role. Growing up through childhood means being condemned to a process of in-human conflict between self-awareness and the role imposed by a society going through its own school age. Stephen Daedalus nor Alexander Portnoy enjoyed childhood, and neither, I suspect, did many of us like to be treated as children. If there were no age-specific and obligatory learning institution, “childhood” would go out of production. The youth of rich nations would be liberated from its destructiveness, and poor nations would cease attempting to rival the childishness of the rich. If society were to outgrow its age of childhood, it would have to become liveable for the young. The present disjunction between an adult society which pretends to be humane and a school environment which mocks reality could no longer be maintained. The disestablishment of schools could also end the present discrimination against infants, adults, and the old in favour of children throughout their adolescence and youth. The social decision to allocate educational resources preferably to those citizens who have outgrown the extraordinary learning capacity of their first four years and have not arrived at the height of their self-motivated learning will, in retrospect, probably appear as bizarre. Institutional wisdom tells us that children need school. Institutional wisdom tells us that children learn in school. But this institutional wisdom is itself the product of schools because sound common sense tells us that only children can be taught in school. Only by segregating human beings in the category of childhood could we ever get them to submit to the authority of a school teacher.”

This particular quote, a clearly radical approach to the place of young people within or outside of a teaching institution, leaves me with a lasting impression that I can reintroduce to my thoughts on David Harding. In place of a segregation of ‘child’ or ‘socially included’ I feel inclined to put my own highlighted phrase ‘individual in their own right’. This I feel implies, in a better way, that the person who is learning is respected firstly as an individual, who is capable of choosing for themselves and who has an interest in what is happening. To add to this I would like to propose that an activity that is pushed and pursued to its utmost, in terms of following interesting notions and developing them, will ultimately appeal to many more people and probably in more surprising ways than can be imagined. In addition to this I will submit a proposal, in a later posting, for an event that could take place in the Dalry school, this will be in a developmental stage in the same way as these thoughts, so please give feedback and comments.

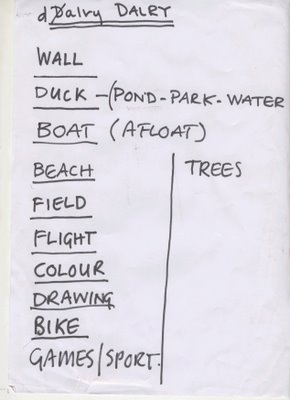

Here is a list of some of the topics we wish to engage with in our upcoming filming session. These have been selected because they are in some way universal subjects, subjects that are not methods, or tools. There was a lengthy debate about whether the categories actually fited our descriptions. I cannot remember the exact point that we came to terms with everything on the list but perhaps you can all add to this explanation. The other image is part of the cover for the DVD proposal.

Here is a list of some of the topics we wish to engage with in our upcoming filming session. These have been selected because they are in some way universal subjects, subjects that are not methods, or tools. There was a lengthy debate about whether the categories actually fited our descriptions. I cannot remember the exact point that we came to terms with everything on the list but perhaps you can all add to this explanation. The other image is part of the cover for the DVD proposal.